Remembering MLK: Leading the Montgomery Bus Boycott With Nonviolence

How the young minister set the tone for future Civil Rights demonstrations

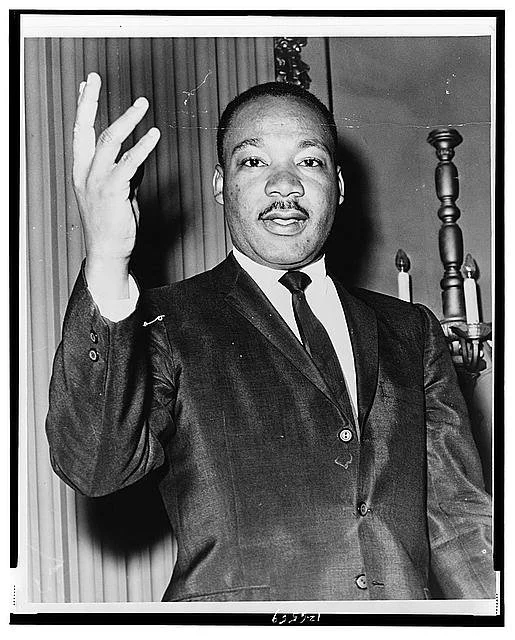

Dick DeMarsico, photographer, 1964. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Prints & Photographs DivisionThe young minister walked four blocks from where he parked, with lines of cars backed up for six or seven blocks in each direction of Holt Street Baptist Church on Monday night. Several thousand people stood outside the church after the sanctuary and basement auditorium were already filled to the brim. The first mass meeting of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) was held on Dec. 5, 1955, and people waited patiently for further instructions on the bus boycott that began that morning. The newly appointed president of MIA was 26-year-old Martin Luther King Jr., the young new minister trusted to lead the Black folk of the city in protest.

King usually needed 15 hours to prepare his Sunday sermon. This time, he ran out of time and only spent 15 minutes mentally preparing a speech for the first mass meeting. The speech would echo to the thousands in attendance and those watching local evening news broadcasts. His words would shape the political action after Rosa Parks was arrested four days prior—all eyes were on King.

“We are here, we are here this evening because we’re tired now,” said King. “And I want to say that we are not here advocating violence.”

Earlier that morning, King and his wife Coretta got ready for the day by 5:30 a.m., earlier than usual. The two waited patiently in the kitchen, waiting for the 6 a.m. bus to arrive at the stop just five feet from their house. As King sipped his morning coffee, Coretta pointed out the window and said: “Darling, it’s empty!” It was day one of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and the South Jackson line—the line with the most Black passengers among all Montgomery lines—had no one aboard.

Just as he preached in the pulpit at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church on Sunday mornings, King emphasized remaining true to strict moral principles at the first MIA mass meeting. Before creating his mental speech outline, he thought to himself: “How could I make a speech that would be militant enough to keep my people aroused to positive action and yet moderate enough to keep this fervor within controllable and Christian bounds?” Christian values shined through his first prominent speech as a civil rights leader, empowering the Black folk of Montgomery while advocating for peaceful means of protest.

“The only weapon that we have in our hands this evening is the weapon of protest,” King proclaimed.

The people responded enthusiastically as King urged them to protest while being driven by love. Attendees rose to their feet and applauded King as he stepped down from the pulpit. King thought God spoke for him that night, evoking more response than any Sunday sermon. Day one of 381 was successful in all of its endeavors—in action and in empowerment.

How the boycott came to be

Bus segregation long stood across the South with laws stating Black folks had to sit in the back and give their seat to white passengers if the front was full. Rosa Parks’ act of civil disobedience on Dec. 1, 1955, was against this very law—a testament to her active leadership within the local NAACP branch. Parks joined the Montgomery NAACP chapter in 1943, the same year she began serving as the branch’s secretary, a position she held until 1956. She helped expand membership and foster youth participation within the organization. At 41, Parks re-founded the Montgomery NAACP’s Youth Council in 1954.

Nine months before Parks, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white woman—an act that would hold more power later on. Parks knew Colvin prior to the teen’s act of resistance, trying to get her more involved in the NAACP Youth Council. The teenager was believed to have a feisty, rebellious spirit, so civil rights leaders decided Colvin wasn’t the person to organize around. Parks was a mentor to Colvin after the teen’s arrest, constantly urging her to share her story of protest with her peers. Parks’ arrest ignited the fire within the Black folks of Montgomery, but how they would use that fire was essential to the movement.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott began when E.D. Nixon, president of the local NAACP chapter, and Jo Ann Robinson, president of the Women’s Political Council, moved quickly to organize a response to Parks’ arrest. The two printed and distributed thousands of leaflets calling for a one-day boycott of the city’s buses on Dec. 5. The Montgomery Improvement Association was created on that first day, where local Black civil rights leaders selected King to lead the effort. King, a young pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, had moved to Montgomery just a year earlier. He was known as a charismatic speaker who was widely respected and had yet to make powerful enemies, factors that contributed to his selection as the boycott’s leader.

Montgomery was a city that already had a strong foundation of civil rights activism. By the mid-1950s, the NAACP had grown increasingly prominent, and the Women’s Political Council had spent years lobbying city officials for improved bus conditions. That history of organizing helped mobilize Montgomery’s politically engaged Black community to challenge the city’s strict bus segregation.

The boycott gained momentum

After that first day, the boycott got organized as it gained more traction. Black leaders organized carpools, Black taxi drivers charged the same fare as bus rides (10 cents), and masses walked the streets of Montgomery. Buses went on their usual routes, but they were mostly empty. The previously loyal riders were among the 75 percent of Montgomery’s bus ridership. Yet, the city refused to comply with the protesters’ demands.

The demands didn’t initially call for a change in segregation laws. MIA issued a list of demands that called for Black bus drivers to be hired, and a first-come, first-served system to be put in place. The Black people of Montgomery unanimously agreed not to ride on the buses in an act of resistance.

Even white sympathizers were moved by the defiant act of protest. A librarian at the Montgomery Public Library, Juliette Morgan, wrote a letter titled “Lesson From Gandhi” to the Montgomery Advertiser.

“It is hard to imagine a soul so dead, a heart so hard, a vision so blinded and provincial as not to be moved with admiration at the quiet dignity, discipline, and dedication with which the Negroes have conducted their boycott,” Morgan wrote.

Each day, the boycott gained momentum under the leadership of King. Still, King himself needed all the help he could get. Bayard Rustin, a renowned civil rights organizer, was a key advisor to King. The War Resisters League, a New York-based organization where Rustin served as executive secretary, sent him on leave to Montgomery in Feb. 1956. Rustin was convinced by his mentor, Asa Philip Randolph, a civil rights leader, and was eager to spread Gandhian philosophy to the Montgomery boycott.

King, 11 years younger, welcomed Rustin’s counsel with years of experience in resistance under his belt. Rustin worked closely with King in Montgomery, offering guidance on nonviolent tactics and organizational strategy. Rustin drew on his involvement in organizing the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, an early effort to challenge bus segregation in parts of the upper South, as well as first-hand contact with the Gandhian non-violent resistance movement in India in 1947.

Rustin met King at his house to be acquainted for the first time in Feb. 1956, eager that King was willing to understand beyond his academic knowledge of nonviolence through Gandhian principles. Upon entering King’s home, Rustin noticed armed guards outside and a pistol lying around the living room.

“We’re not going to harm anyone unless they harm us,” said King after Rustin asked about the weapons.

In that moment, Rustin knew King had a lot to learn. Together, they studied Gandhi enough for King to meld aspects to Christian values that the participants were receptive to. King increasingly studied the writings of Gandhi and began referencing him more frequently in his speeches and sermons. He also gave up the gun he had purchased for personal protection and instructed those guarding his home to disarm themselves.

Rustin only spent a few months in Alabama, hiding out in Birmingham most of the time while studying with King. Rustin was sent back to New York, his homosexuality and communist affiliation ultimately deemed a detriment to the movement by the War Resisters League. He set up discreet communication lines to King and other boycott leaders before he left Alabama, making sure he could still support the boycott from New York. After he left Alabama, Rustin still felt the power of the people of Montgomery.

In September 1956, Rustin stated in a letter to King that he would be a spokesperson for the Montgomery boycott in Philadelphia during a Consultative Peace Council meeting, comprised of major peace organizations in the country at the time. This letter was obtained in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center.

“This will do more than anything else to get these organizations working more vigorously in the interest of the Improvement Association,” wrote Rustin.

He wanted King to provide him with first-hand updates on the progress of the protest, so he could lead the discussion in Philadelphia in the interest of MIA.

“Even those who were willing to get their guns in the beginning are gradually coming to see the futility of such an approach,” King wrote to Rustin.

The participants of the boycott in Montgomery had a growing commitment to the philosophy of nonviolence, even when the white opposition tried to dull their flame. Rustin wrote a “Montgomery Diary” that was published in the April 1956 issue of an independent monthly magazine called “Liberation.” Rustin detailed a week in late February in Montgomery during the boycott.

Upon observing a MIA meeting, he wrote: “As I watched the people walk away, I had a feeling that no force on earth can stop this movement. It has all the elements to touch the hearts of men.”

White opposition targets boycott leaders

On the night of Jan. 30, 1956, hundreds gathered outside the front porch of the King family home. Montgomery police swarmed the house as the crowd of Montgomery residents was riled up. Coretta King and Yolanda, the King’s 10-week-old daughter, were inside with the police in a state of fear.

Meanwhile, King was speaking at the close of a MIA meeting and collecting donations for the boycott from attendees. All in a few moments, ushers rushed in and out of the aisles, glancing at King for a brief second at a time. One even tried to get his attention, but was sent away by a clergyman. Now, obvious that the matter concerned him, King demanded someone tell him what was wrong.

“Your house has been bombed,” said Ralph Abernathy, co-founder of MIA.

King asked if his wife and child were okay.

“We are checking on that now,” Abernathy responded.

King rushed home in about 15 minutes to find the crowd surrounding his house. When he stepped inside, he found Coretta and baby Yolanda in a bedroom unharmed. King could finally exhale—his family was okay.

On the front porch, a police officer pointed to a spot where a bomb had exploded. The front windows were shattered, and the wood front porch was splintered open. King heard the crowd outside filled with rage and wrote in his memoir, “Nonviolent resistance was on the verge of being transformed into violence.”

The police failed to disperse around 300 people outside; the Black Montgomery residents demanded justice. They wanted revenge for the act of racial violence, and some carried knives and guns to show just how serious they were.

Even when his family was victim to an almost fatal attack, King felt he needed to calm and remind people of the key principle of the boycott.

“If you have weapons, take them home; if you do not have them, please do not seek to get them. We cannot solve this problem through retaliatory violence,” he said.

Only two days later, Nixon, president of the Montgomery NAACP chapter and another key organizer of MIA, found his yard had been bombed. In August, another bomb detonated on Robert Graetz’s front porch—a white minister and member of MIA. No one was arrested, charged or convicted for these attacks, even when the police offered the public a $500 reward for evidence regarding the King house bombing. The mayor at the time even publicly announced that it was a publicity stunt done by the protesters. Reaction forces were instilling fear into the boycott leaders, and they had no authorities to protect them.

King took it to the highest man he could think of besides God himself—the president. He wrote to President Dwight Eisenhower two days after Graetz’s house was bombed, urging an investigation to be made so justice could be served. The letter was obtained in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center.

“The ‘don’t care’ attitude of public officials toward such violence is manifesting itself throughout the city and state and encouraging hoodlums to continue,” King wrote. “If something is not done to put a stop to it, further violence can be expected.”

All that was heard back regarding this violence was: “The information concerning the alleged violence, the activities of the White Citizens Council and the local officers, does not appear to indicate violations of federal criminal statutes.” Assistant Attorney General Warren Olney wrote this in a letter back to King, seemingly more concerned about the Black voter suppression King mentioned briefly. The letter was obtained in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center.

White opposition continued to find ways to hinder the boycott in Montgomery. In February 1956, Alabama officials reached for a decades-old statute—one rarely used, buried in legal code since 1921. Prosecutors charged Martin Luther King Jr. and 80 other leaders of the bus boycott under a law prohibiting conspiracies that interfered with lawful business. By walking instead of riding the buses, Montgomery’s Black residents were breaking the law.

King was the first to face trial on Mar. 18, three months into the boycott. The courtroom was packed with reporters and spectators, the audience being a reminder that a local protest had become a national story. King had eight different lawyers over the course of his four-day trial, with 31 Black witnesses testifying to harassment they experienced on Montgomery buses. Still, the jury found him guilty.

Upon hearing his verdict, the judge fined King a total of $1000—$500 as punishment and $500 for court fees. King appealed the court decision, which meant he faced the risk of 386 days in jail. He was released on bond and eventually only had to pay a fine a year later when his appeal was rejected. The state expected to weaken the movement by making an example of its young leader. But instead of shrinking into shame, the moment emboldened him.

King stepped out of the courtroom and into the glare of dozens of cameras, with camera flashes going off and reporters shouting questions. His calm demeanor signaled that the struggle in Montgomery was far from over. For the boycott organizers, the conviction only underscored what they were fighting against.

"This will not mar or diminish in any way my interest in the protest," King said outside the courthouse. "We will continue to protest in the same spirit of non-violence and passive resistance, using the weapon of love."

Despite the intimidation of Montgomery authorities, the movement held strong. Day after day, thousands walked the streets. The entire backbone of Montgomery’s Black community powered the protest with determination and blistered feet.

Montgomery’s legal battle

While the state targeted boycott leaders with arrests, lawyers representing Montgomery residents quietly attacked segregation at its source. Leaders of the boycott discussed filing a federal lawsuit, hours before King’s house was bombed in late January, on behalf of five female plaintiffs who were mistreated on Montgomery buses—one of them being teenager Claudette Colvin. Fred Gray and Charles D. Langford, civil rights lawyers, filed Browder v. Gayle on Feb. 1, 1956, which challenged the constitutionality of bus segregation.

The two counselors argued the case with the aid of Thurgood Marshall, the renowned civil rights lawyer who successfully argued Brown v. Board of Education, and other NAACP attorneys. They had to prove that the segregated bus system in Montgomery was unconstitutional, which would set a nationwide precedent to end bus segregation.

National media turned Montgomery into a symbol of the country’s racial divide. King, once a new Montgomery pastor, was emerging as the steady voice of a rising movement. All eyes were on Montgomery as the boycott held strong for almost a year already.

On Nov. 13, 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled bus segregation unconstitutional. The city of Montgomery had lost its fight to preserve the old order.

Celebration erupted through the Montgomery Black community. King reminded them that the victory was not just for Montgomery, but for all who believed in justice through peaceful means. MIA ordered the Black folks of Montgomery not to return to the buses until the Court’s decision was implemented for their safety.

King boarded a bus a month later on Dec. 21, 1956. Cameras followed as he paid his fare, walked past the first rows where white passengers once sat, and took his place toward the middle. It was a simple act—but a monumental symbol. Black and white riders filed in behind him, sharing a public space that had once symbolized humiliation.

The success of the boycott had not erased the racism that kept Montgomery divided, but it proved that nonviolent resistance was effective. Montgomery became the blueprint.

King’s impact on Montgomery

King’s leadership during the 13-month protest launched him onto the national stage. Nonviolent protest became the core strategy of the expanding Civil Rights Movement—from sit-ins, to Freedom Rides, to the March on Washington. Today, peaceful demonstrations continue to shape American politics, even as activists still face sweeping crackdowns and militarized government responses in some cities.

The boycott did not end division in America, but it permanently shifted the balance of power, showing that people unified in one goal could create change peacefully.

King would later write of that first day of protest in Montgomery: “That night we were starting a movement that would gain national recognition; whose echoes would ring in the ears of people of every nation; a movement that would astound the oppressor, and bring new hope to the oppressed. That night was Montgomery’s moment in history.”